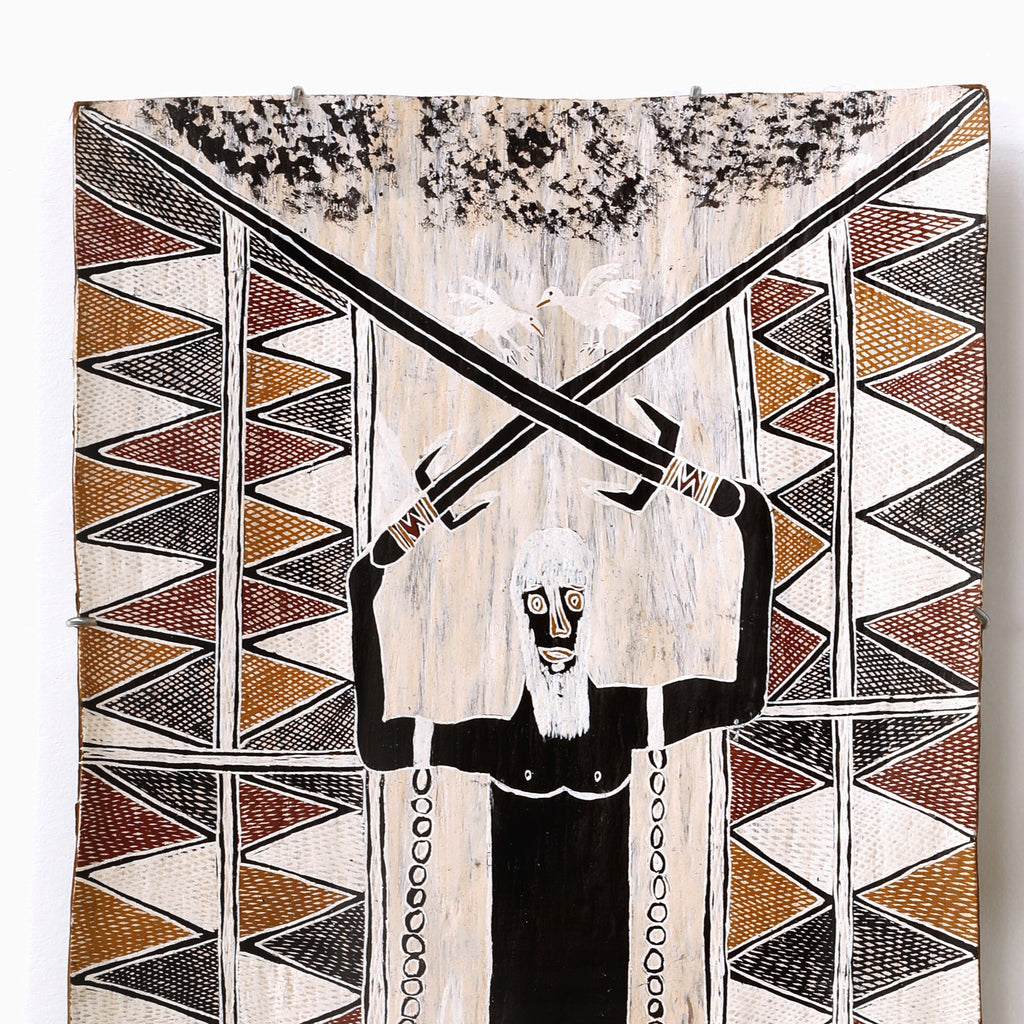

Gamanarra Wunuŋmurra, Gurrumuru Birrinydji, 128x62cm Bark

Your support helps the artist and their community art centre.

Free insured post & 120-day returns Ships from Tasmania within 1 business day Arrives in 1–3 days (Aus) · 5–10 days (Int’l*) Guaranteed colour accuracy

Community Certified Artwork

This original artwork is sold on behalf of the community-run art centre. It includes their Certificate of Authenticity.

– Original 1/1

- Details

- Artwork Story

- Bark Process

- Artist

- Art Centre

- Aboriginal Artist - Gamanarra Wunuŋmurra

- Community - Yirkala

- Homeland - Waṉḏawuy

- Aboriginal Art Centre - Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre

- Catalogue number - 2547-18

- Materials - Earth pigments on Stringybark

- Size(cm) - H128 W62 D3 (irregular shape)

- Postage variants - Artwork posted flat and ready to hang with a metal mount

- Orientation - As displayed

This work discusses events that happened at Gurrumurru involving the ancestral spirit Birrinydji. The miny’tji or cross-hatched design is a sacred signature that embodies the outside story and the non-secular. This painting was first revealed publicly in 2008 by artist Yumutjin Wunuŋmurra and a recording was made of the artist talking about it. Although there is no direct reference to the associations Yolngu had with the seafaring Maccassan the translation is obvious that the ancient songlines of the Dhalwangu clan contain strong elements of the Indonesian annual visitations to this region. The mere mention of steel knives, pillows, tobacco, cards, money, and alcohol in these songs enforce the anthropological record of Maccassan visitation over the centuries up until the very early 1900s. Yolng dancing this story also action the events of below.

Translated: This is my home and this is a songline about Gurrumuru. Birrinydji the warrior thinks about knives. These songs contain deep names of the spirit of Birranydji. People went out with Birranydji to clear an area, prepare it, to make it straight, to make it special, to make it sacred, a place where Dhalwangu can be attached. After the clearing, they walk over the paths finding a large shady tree where the work done was assessed. While resting Birrinydji put his head down on a pillow and slept. On waking and yearning for tobacco he smoked. After smoking they played cards where he won money. With his winnings, he went to the main house and bought things on offer. Here he bought grog and on drinking it felt the desire to dance. He danced with the knives as if a shadow boxer. After the dance, they cooked rice which they put out on arranged plates. When eating was over in the afternoon the leftovers were thrown on the ground. Smelling this the scrub fowl Djilawurr came in to eat bringing the north wind Lungurrna with him. This marked the end of the day with the sunset of Djapana.

In many ways, the harvesting and material production to create bark paintings is an art in itself. The bark is stripped from Eucalyptus stringybark. It is generally harvested from the tree during the wet season. Two horizontal slices and a single vertical slice are made into the tree, and the bark is carefully peeled off. The smooth inner bark is kept and placed in a fire. After firing, the bark is flattened and weighted to dry flat. Once dry, the bark becomes a rigid surface and is ready to paint upon.

Djawakan Marika, Yilpirr Wanambi, Wukun Wanambi and Nambatj Munu+ïgurr Harvesting stringybark for artists Photo credit: David Wickens

Wanapa Munu+ïgurr, Yilpirr Wanambi and Wukun Wanambi harvesting stringybark. Photo credit: David Wickens

Wanapa and Nambatj Munu+ïgurr firing a bark to start the flattening process. Photo credit: David Wickens

Arnhem Land paintings are characterised by the use of fine crosshatched patterns of clan designs that carry ancestral power: the crosshatched patterns, known as rarrk in the west and miny’tji in the east, produce an optical brilliance reflecting the presence of ancestral forces.

These patterns are composed of layers of fine lines, laid onto the surface of the bark using a short-handled brush of human hair, just as they are painted onto the body for ceremony.

Rerrkiwaŋa Munuŋgurr painting her husbands design Gumatj fire or Gurtha. Photo credit: Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre

The artist’s palette consists of red and yellow ochres of varying intensity and hues, from flat to lustrous, as well as charcoal and white clay(pictured above). Pigments that were once mixed with natural binders such as egg yolk have, since the 1960s, been combined with water-soluble wood glues.

Naminapu Maymuru White collecting gapan white clay used for painting. Photo credit: Edwina Circuitt

Details are currently unavailable

Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre is the Indigenous community-controlled art centre of Northeast Arnhem Land. Located in Yirrkala, a small Aboriginal community on the north-eastern tip of the Top End of the Northern Territory, approximately 700km east of Darwin. Our primarily Yolŋu (Aboriginal) staff of around twenty services Yirrkala and the approximately twenty-five homeland centres in the radius of 200km.

In the 1960’s, Narritjin Maymuru set up his own beachfront gallery from which he sold art that now graces many major museums and private collections. He is counted among the art centre’s main inspirations and founders, and his picture hangs in the museum. His vision of Yolŋu-owned business to sell Yolŋu art that started with a shelter on a beach has now grown into a thriving business that exhibits and sells globally.

Buku-Larrŋgay – “the feeling on your face as it is struck by the first rays of the sun (i.e. facing East)

Mulka – “a sacred but public ceremony.”

In 1976, the Yolŋu artists established ‘Buku-Larrŋgay Arts’ in the old Mission health centre as an act of self-determination coinciding with the withdrawal of the Methodist Overseas Mission and the Land Rights and Homeland movements.

In 1988, a new museum was built with a Bicentenary grant and this houses a collection of works put together in the 1970s illustrating clan law and also the Message Sticks from 1935 and the Yirrkala Church Panels from 1963.

In 1996, a screen print workshop and extra gallery spaces was added to the space to provide a range of different mediums to explore. In 2007, The Mulka Project was added which houses and displays a collection of tens of thousands of historical images and films as well as creating new digital product.

Still on the same site but in a greatly expanded premises Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre now consists of two divisions; the Yirrkala Art Centre which represents Yolŋu artists exhibiting and selling contemporary art and The Mulka Project which acts as a digital production studio and archiving centre incorporating the museum.

Text courtesy: Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre

"This is my third artwork purchase from Art Ark, and I am thrilled to bits with every one of them!" - Gabrielle, Aus – ART ARK Customer Review