Artist Nyapanyapa Yunipingu is assisted by art centre worker Jeremy Cloake at Buku-Larrnngay Art Centre, Yirrkala. Siobhan McHugh

Siobhan McHugh, University of Wollongong and Ian McLean, University of Melbourne

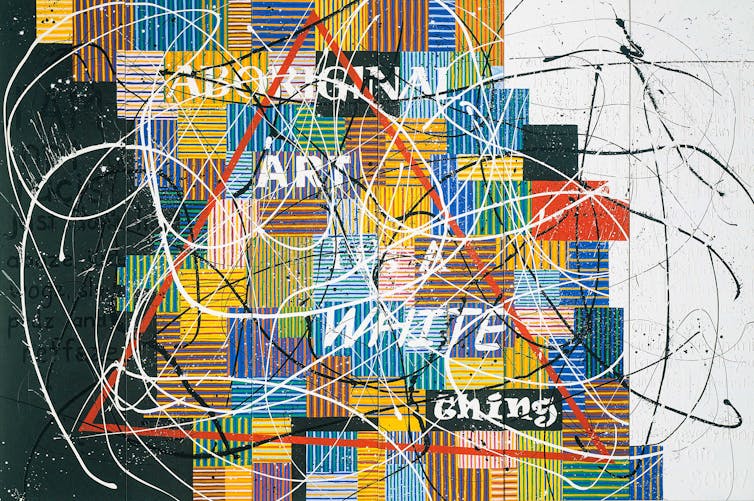

“Aboriginal Art – it’s a white thing” … so Brisbane Aboriginal artist Richard Bell declared in 2002. Bell’s accusation that a white industry controls all aspects of Aboriginal art, even shaping its production through demand for particular types of work, hit a raw nerve that still makes people jump – still, because the same system is in place.

However, like most things, the deeper you dig into this white thing the greyer it becomes. Our research sought to unpack the relations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous players in this lucrative industry by investigating three of the most successful organisations selling Indigenous art in Australia today (measured by dollar value of sales): one in Arnhem Land, one in Central Australia and one in Brisbane that specialises in urban Indigenous art. Visiting each, we interviewed its invisible white workers and very visible Indigenous artists, intent on hearing their voices.

Brisbane’s Milani Gallery, which represents Bell, is owned and run by Josh Milani. Trained as a lawyer, Milani sees his role “as an advocate – I do it with a sense of moral purpose and hopefully integrity”.

Growing up with an Italian migrant father, Milani always “felt like a Wog”. His natural empathy with outsiders and intellectual passion for art and justice led him to where he is now: the go-to Australian dealer in contemporary art for international curators. “I’ve learned a lot – how power operates, identity operates,” he says.

Issues of power and identity are equally fundamental to the art produced at Buku-Larrnggay Mulka, a Yolngu-owned-and-run art centre in Yirrkala, 600 kilometres east of Darwin. Its art also comes from the artists’ lived experience, in an unusually intact and vital Yolngu culture.

Will Stubbs, a former criminal lawyer from Sydney, has been employed to manage the centre for over 20 years. His brief: to balance cultural imperatives with market demand. “They (the artists) bring in what they want to bring in, not what we ask for. And then we have to make it work from there” – in, that is, the white market and art world.

One of Buku-Larrnggay’s most successful artists is Nyapanyapa Yunipingu, a fixture in the centre whenever it’s open. One wet season the centre ran out of bark and, to keep her busy, Stubbs handed her some acetates and a paint pen – leftovers from a failed animation project. As the acetate paintings accumulated, he noticed “this filigree of complexity, of abstract existence, that I’d never seen before”.

Stubbs realised that seeing the paintings in random permutations and sequences would accentuate their impact – so he contacted a Melbourne digital guru, Joseph Brady, who could devise such an algorithm. The result was Light Painting, five editions of a looped silent digital file. It was installed in the 2012 Sydney Biennale.

Brady became so affected by Yolngu culture that he transplanted his young family to Yirrkala, where he now manages the Mulka Project at the art centre, a vast digital archive of Yolngu knowledge.

Read more: Friday essay: how the Men's Painting Room at Papunya transformed Australian art

The artists we spoke with at Yirrkala were very happy with the art centre. “I love how art is carrying me out to the world,” says artist and elder Garawan Wanambi – whom Milani also represents. “I thank Will Stubbs, how he supports me and the art people … and how we respect each other and communicate…”

‘So long as it sells’

The Warlpiri-run Warlukurlangu Centre at Yuendemu, 300 kilometres northwest of Alice Springs, is also defying the post-GFC downturn in the Aboriginal art market. For over 15 years, it has been run by two Chilean women. “They hired me because I’m an outsider,” says Cecilia Alfonso. “They don’t want some hippie-dippy well-intentioned person to run their business … I could sell rice to China!”

Alfonso and her business partner, Gloria Morales, monitor the market closely. The centre turns over about 8,000 artworks a year, compared to around 300 when they started.

Traditional owner and artist Andrea Nungarrayi Martin is unconcerned whether the artists paint their traditional “tjukurrpa” or dreaming story, or decide to do something non-sacred. “Doesn’t matter – so long as it sells,” she told us. It’s another twist in the “authenticity” debate around Aboriginal art.

In 2002 Bell decried how the white-controlled Aboriginal art industry privileged art from remote areas as more “authentic” than that from urban areas. Vernon Ah Kee, another successful artist in Milani’s gallery, agrees: urban Aborigines “are as much Aboriginal as anybody else” and, adds Bell, “we paid the biggest price” for colonisation.

The genius of Ah Kee and Bell is to leverage this immense loss into a return. “When I started working with Richard [in 2003], we were selling paintings for $2000,” recalls Milani. But “the more … he offended [my white clientele], the more I put his prices up!” And the more they sold.

“I consider myself an Aboriginal artist because I make art from an Aboriginal context,” says Ah Kee. “Not one minute in my life have I been permitted to declare myself Australian. So … I choose to be completely Aboriginal.”

Though he believes that the Aboriginal art industry “exists almost as a completely white construction”, he is very happy with Milani. “He understands what I want to do … I feel I can just do whatever I like and it’s his job to sell whatever I make.”

Brilliant as these white dealers are, they need the artists as much as the artists need them.![]()

Siobhan McHugh, Associate Professor, Journalism, University of Wollongong and Ian McLean, Professor, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.