** **We’re all, it seems, familiar with the terms “Dreamtime” and “The Dreaming” in relation to Aboriginal Australian culture, but – as I noted in the first part of this series – such terms are grossly inadequate: they carry significant baggage and erase the complexities of the original concepts.

So how did this terminology enter the English language?

In the late 19th century Francis Gillen, the post- and telegraph stationmaster in Alice Springs – an Arrernte speaker (spelled Arunta at that time) and keen ethnologist – became the first person on record to use the expression “dream times” as a translation for the complex Arrernte word-concept Ülchurringa (“Alcheringa”; “Altyerrenge” or “Altyerr”), the name of Arrernte people’s system of religious belief.

Gillen, who had begun working in Alice Springs in 1892, collaborated with Walter Baldwin Spencer, a Lancashire-born biologist and anthropologist in “studying” the Arrernte. By all accounts, Gillen had forged mutually respectful relationships with the local Arrernte people.

Baldwin Spencer popularised Gillen’s words in his 1896 account of the Horn Expedition. Without academic endorsement by someone of Baldwin Spencer’s standing, Gillen’s translation would in all likelihood never have taken off, let alone entered populist discourse.

So the term owes its credibility and contemporary ubiquity to Baldwin Spencer and the other anthropologists who followed him in using words or expressions that included the morpheme “dream” as a generic translation for all Indigenous Australian belief systems.

Subsequent to that 1896 publication, variants based on Gillen’s usage have become integral to almost all of the English words or expressions used to describe Australian Aboriginal religion.

“The Dreaming” and the politics of translation

Initially the uptake of Gillen’s terminology was gradual, but it morphed over time into “Dreamtime”. In A. P. Elkin’s 1938 book The Australian Aborigines: How to Understand Them, the anthropologist began using “Dreamtime” more or less interchangeably with “Dreaming”.

But it was undoubtedly the esteemed Australian anthropologist W.E.H. Stanner who gave the term “The Dreaming” the fillip it needed to propel it into the broader English lexicon. Since then, “Dreamtime”, “Dream Time” or “Dreaming” have been widely deployed as generic names for all systems of Aboriginal religious practice. This is reflected in the widespread usage of this terminology today.

These terms have also entered many other world languages: most now use the nominal “dream” somewhere in the word or words used to convey the concept.

In French, such language use is evident in academic articles such as Espaces de rêves (1983), by French anthropologists Félix Guattari and Barbara Glowczewski, and in Glowczewski’s 1989 book, Les rêveurs du désert - peuple warlpiri d'Australie. The title refers to Warlpiri people as “dreamers of the desert”.

In a recent communication, a Croatian colleague of mine working in Australian Studies at the University of Zagreb, Dr Iva Polak, wrote about the challenges she faced in translating the concept of “The Dreaming”:

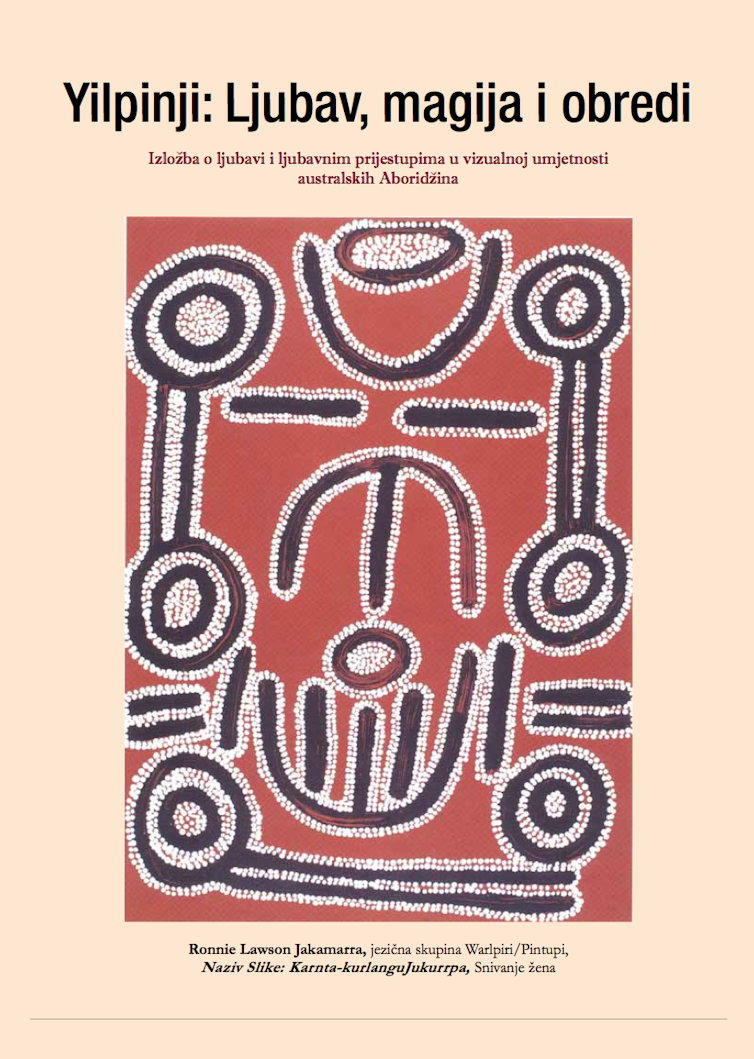

In Croatian I (as the only person working in this academic field) translate The Dreaming as Snivanje, which is a gerund form. The morpheme is “san”. Its etymology is Old Slavonic or more specifically Latin (somnus).

The direct derivative gerund from “san” would be sanjanje, which directly connotes having dreams while you sleep. This is why I go for Snivanje and the plural form Snivanja (to indicate the pluralism of the concept), which is less frequent in usage and might at least cause a certain degree of defamiliarisation in readers’ minds.

Moreover, there’s no way in the world that you will hear that word in everyday usage, unlike the English “dreaming”. However, every time you want to write about it in Croatian, it’s useful to indicate immediately that this is a flawed term based on the English term “Dreaming”.

Dreams and “The Dreaming”

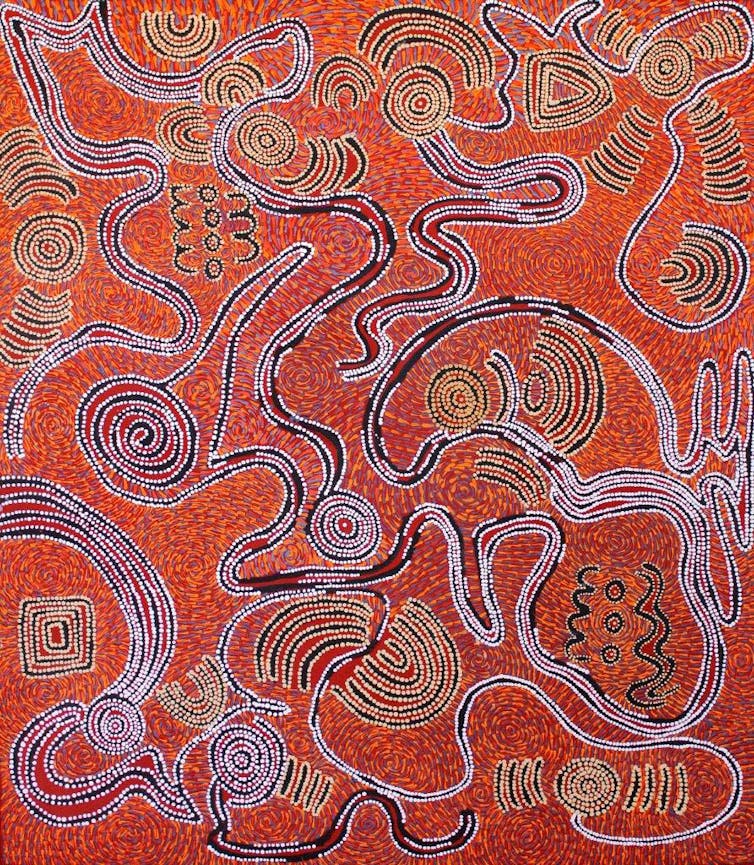

Admittedly, in traditional Aboriginal life-ways dreams are attributed with potent power. On occasion new narratives, songs, dances and ceremonies can be introduced via dreams, but this is by no means an everyday occurrence and is just one strand of the complex concept that has become so widely known as “Dreaming”.

Unfortunately, the dream-related terminology serves to erase the complexities of the original concepts in the many different Indigenous languages and cultures, by emphasising their putatively magical, fantastic and illusory attributes, when The Jukurrpa, Altyerr, Ungud, Ngarrankarni, Manguny, Wongar, and so forth are understood by their diverse Aboriginal adherents to be reality, religion, and the Law.

These are religions grounded in the earth itself, which provide a total epistemological and ontological framework accounting for every aspect of existence.

“Dreaming Ancestors” and “Dreaming Narratives”

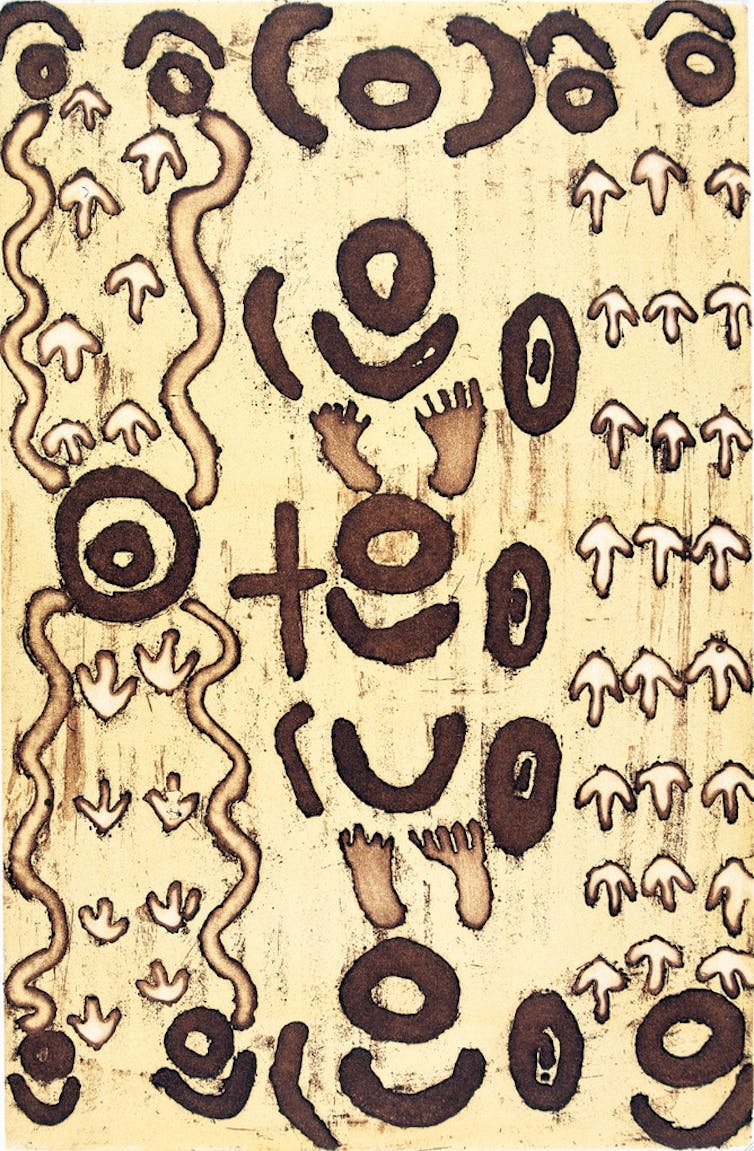

Dreamings are Ancestral Beings associated with life forces and creative powers, knowledge of which is on occasion communicated to people by means of dreams. Invisible beings, with diverse names across the different language and cultural groups, carry around knowledge of these beings.

As stated previously, the rituals, visual art designs, songs, dances, places and ceremonies associated with these beings can be – although are not routinely – communicated to people through their dreams while they sleep.

The “Dreaming” and the actions and behaviour of the Ancestral Beings, who are in and of themselves “Dreamings”, provide models or templates for all human and non-human activity, social behaviour, ethics and morality.

Importantly, Dreaming Narratives also have encoded in them important information regarding local micro-environments, including local flora, fauna and the location of water, deep knowledge of “country”, and survival in specific locations.

As such, “Dreamings” are significant means of intergenerational knowledge transmission, which in pre-contact days occurred entirely by word of mouth.

It also needs to be noted that Dreaming Ancestors frequently behave badly, acting as what could be described as “negative exemplars”. In this regard, these often-flawed Dreaming Ancestors may be regarded as structurally similar to the Greek gods – although Dreaming Ancestors are not gods, because The Dreaming is neither a monotheistic nor polytheistic religion.

These Creator Ancestors frequently exhibit shabby, even at times socially-transgressive, tendencies, mirroring the less savoury attributes of human behaviour, including lust, greed, a will to power, violence, bloodthirstiness, the ill-treatment of women and young girls, and worse.

(Other religions – including Christianity, through the Bible – are sources of somewhat structurally similar approaches. “Thou Shalt Not …” frames most of The Ten Commandments.)

Dreaming Narratives act as vehicles for identifying both appropriate and inappropriate human behaviours. In practice, that means illicit or forbidden activities, base deeds and other forms of destructive human conduct are identified, condemned and proscribed as existing outside of the boundaries of Indigenous law.

“Dreaming” is not conceived as belonging in a historical past as is, say, the case with the Biblical book of Genesis, with which the concept is sometimes compared on account of its foundational Creation narrative. There’s some degree of overlap with the Biblical Genesis, however, in terms of the originary creative activity of Dreaming Ancestors.

While the period of creation in Genesis is understood to have occurred in the past, “The Dreaming” is conceptualised as an eternal and continuing process involving the maintenance of life forces, embodied or symbolised as people, spirits, other natural species, or natural phenomena such as rocks, waterholes or constellations.

In certain parts of Australia, “Dreamings” may be fishes or other sea creatures. A “Dreaming” may be an animal, a reptile, insect, a human Ancestor, or a type of flora.

Bush-medicine vines, bush bean trees, or what’s often generically and simplistically designated as “bush tucker” in titles of artworks, various kinds of yams, bush berries, bush tomato, bush onion – all of these and more feature. Other parts of the natural world or environment that are also “Dreamings” include water, specific waterholes, stars or constellations (the Seven Sisters, or Milky Way, for instance).

A “Dreaming” may be a shape-changer and manifest itself in various different ways or forms – for example, as a human but also a tree, star, or even a mosquito.

In terms of English language use, the idea of “Dreaming” has now firmly taken hold, when it would be more accurate and respectful for all Australians to learn – and to use – local Indigenous language terms for this complex concept.

As nursing Sister Ellen Kettle, who was for many years posted at the Warlpiri settlement of Yuendumu, wrote in 1952:

… white newcomers have assumed the right to rename almost everything.

This article is the second in a series on “Dreamtime” and “The Dreaming”. Read part one here and part three here.![]()

Christine Judith Nicholls, Senior Lecturer , Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.